Claire Porter

Great Divide

Days Passed

Days Passed

Days Passed

Days Passed Days passed, and I didn’t budge an inch on the map. I hovered at the Wyoming-Colorado border in the teeny town of Savery, Wyoming, my progress impeded by an injured ankle. Three days of pedaling three digit mileage had taken its toll on my body, when all I wanted to get out of the waterless, hallucination-inducing Great Divide Basin of Wyoming. I made it out of the Basin, but the morning after that third century day I awoke in a tepee with a swollen Achilles tendon that protested walking, squatting, and especially pedalling a mountain bike laden with gear. I didn’t realize the severity of the injury when I left the tepee at the Little Snake River Museum (third time sleeping in a tepee on this trip!), and when I bid the lovely museum ladies adieu, I thought I would never see them again. After painfully pedaling 6 miles to the tiny post office in Slater, CO, I sat at the border and contemplated my situation. Clearly something was up with my ankle, but there was a fire raging within me, that would only be exhausted once I hit the Mexican border. I had to feed the fire, I had to keep pedaling. But at the same time, the Achilles tendon in my left ankle yelped every single pedal stroke- even on the flat terrain. I knew I had over 10,000 feet of climbing to get through in the coming weeks, and if I tore my Achilles that would put out the entire trip. Worst case scenario- my Achilles would rupture in the middle of the desolate mountains preventing me from pedaling- or even walking. It might be days before someone crossed my path, or even weeks, and what if I was far from a water source or I ran out of food…. I shuddered. The decision was clear- I had to return to Savery and give my ankle some needed rest to repair the damage I had done to the tendon from three days in a row of high mileage. As I turned around on the rare bit of pavement, I winced as I passed the sign that jeered, “Leaving Colorado- Entering Wyoming”. It’s just a sign- I told myself. I hoped it wasn’t a sign that my trip was coming to an end.

The museum ladies were surprised to see me again. I approached them like a dog with its tail tucked between its legs, embarrassed to be returning so soon. I explained my situation, and the museum director, a lanky woman named Lela with a long silver braid and huge blue eyes invited me to stay with her. That evening, she announced that I had picked the perfect day to stay with her, as I was about to join her for a “rim picnic” on Brown’s Hill with some of her longtime friends. My eyes bugged out of my head when I learned that one of the guests was no other than Jonathan Boyer- the first American to compete in the Tour de France. The middle-aged man was sinewy and tan, and his stories of racing (and winning) the Race Across America multiple times were overwhelmingly inspiring, but as the night went on he shared gross tales of what happens to the body’s digestive system after being subjected to such grueling work. I won’t get into the details. I couldn’t believe it. If I hadn’t turned around and retreated back t

o Wyoming, I never would have met Jonathan. The fire crackled, and I felt that maybe my injury wasn’t so bad after all.

I ended up spending an entire week with Lela at her ranch- I slept in a sheep wagon under a mound of thick, soft, blankets, I spent the day icing my ankle and picking fresh vegetables from her greenhouse, and I read books from her plentiful collection. I also fretted about what I was going to do with my life after I finished this trip, and the greater worry that consumed me was the sneaking suspicion that my ankle injury would keep me from finishing the Divide. To keep these fears at bay, I offered help to Lela in exchange for letting me stay at her ranch: I picked green beans and attacked weeds with a ferocity that yielded bag after bag of harvested crops to be pickled, steamed, frozen, and given to neighbors. I cleaned her kitchen, something I have to drag myself to do for myself but came easily to me when I knew I was doing it for Lela. Every evening, when she returned from work, we would prepare dinner together and swap entertaining stories- mine of bike tours present and past, and hers of growing up in V

ermont and moving to Wyoming as a young woman to work on a ranch. She never left. One night, she asked me if I knew how to drive a manual transmission car. I joked that I barely knew where the steering wheel was, and at that we got up from the dinner table and strode over to the Isuzu Trooper that sat rusting on her property. I climbed behind the wheel and only managed to stall the engine a handful of times as I learned how to engage the clutch and shift gears on the steep gravel roads that ran around the surrounding hills. When I had first arrived at Lela’s, I felt like a bit of failure for having to take a break from my adventure, but as the days passed and I hadn’t moved one mile on the map, I realized that there is more to be gained than mileage when living on the trail.

After an entire week of driving lessons, bean picking, and waking up in a sheep wagon, I felt anxious to get back on the trail, realizing that it was already mid-September and the nights were only going to get colder. I enjoyed Lela’s company immensely, but the fire within me urged me to get back on the trail, but offered no heat to supplement my sleeping bag (rated 35 degrees F). The morning I left Lela’s ranch, she asked me if I was sure I was ready to leave, and assured me that I could stay as long as I wanted. “But if you’re still here in the winter- I’m going to put you to work chopping wood,” she said with a grin. I laughed, but her comment made me question my decision to take off. I wasn’t certain at all that I was making the right decision. I felt unsteady, and extremely nervous that I was doing more damage than good to my body by choosing to continue riding. After a week of rest, I rolled away from Savery, feeling slow, alone, and vulnerable. At least there was no pain- yet.

Why had I left Lela’s? The fire within me danced, overjoyed to be riding again, and its heat overwhelmed the scant thoughts I had about taking it easy. It was this fire that had pushed me to ride three 100 mile days in a row, which has injured me in the first place. I helplessly took seat beside this internal fire, pedaling onward, and not looking back.

Two days later, not even the bonfire of desire to complete the Great Divide could outshine the reality that my ankle situation was serious. My first day in Colorado I slogged through the mud, a mucky sea of brown glue that lowered both my average speed and my morale. The pain in my ankle was growing, and when I reached Steamboat Springs, CO, I was nearly in tears from the severity of the pain. My Achilles tendon was a stick of string cheese, and each mile I felt invisible fingernails tearing off one thin strand at a time. It was horrible. I limped into town, and tried to smile when I came upon a bike shop that looked like a giant termite mound. I met a group of guys on Bridgestones, Niners, and Soma bikes who had just finished a short 300 mile road tour in the Rockies. We chatted for a bit, and they told me I should check out Kent Erickson’s shop just around the corner. When I stared at them blankly, they hinted, “As in the founder of Moots? He makes custom titanium bikes?” Of course I’d heard of Moots! I eagerly walked around the corner, and met the man behind the gorgeous titanium bikes. Kent is a friendly, quirky guy, and he invited me to camp out at his place since the only legal place to camp in Steamboat was at a KOA several miles out of town. I accepted his offer, and over dinner he told me stories of racing with Greg Lemond and once again I felt like my injury was yielding some good- it forced me to slow down, which opened up opportunities to meet with people who had such amazing stories to share.

I woke up, tested out my ankle with a few foot circles, and the responding pain was enough to put out the fire that had kept me going all these miles. At this point, I had passed the halfway mark of the Great Divide, and while I had covered over 1,500 miles I still had over a thousand to go, and the mountain passes that lay ahead were higher than the ones I had conquered in Montana and Wyoming. The fear of rupturing my Achilles in the middle of the Colorado Rockies, or somewhere in the desolate New Mexican desert was enough to fully extinguish the fire that had kept me going all this time. I had to stop. This was it for me- it just didn’t make sense to try to press on and finish the Great Divide with the risk of my foot falling off.

When I informed Kent of my decision, he gave approval and told me that a ruptured Achilles is a nasty injury that can take many, many months to heal. “If I were you, I wouldn’t risk it. And I’ve done some pretty stupid things,” he laughed. One of his employees was driving to Denver the next morning, and he dropped me off on top of a mountain along the way and I coasted down to the college town of Golden, CO, where my stepsister lived and was attending grad school at School of Mines. As I descended, I felt carefree for the first time in what felt like forever. The last few weeks of injury had weighed heavily on me. I caught views of Denver and Boulder, and as I wound down the mountain, I could make out the giant Coors brewery and the School of Mines campus. My stepsister and her housemates had cleared a mattress-sized space in their bike room for me to sleep, and I crashed on their floor for a week, which led to two weeks, and I spent time icing my ankle, helping cook meals, and something I never would have ex

pected- rock climbing for the first time. Rock climbing didn’t hurt my ankle, as long as I didn’t put all my weight on my left foot, and I quickly fell in love with the sport. It seemed natural for me to take a liking to it- what drove me to pursue the Great Divide was my love of the outdoors and a desire to experience nature in a pure and simple form. One of my stepsister’s housemates had plenty of spare time, so he took me out climbing nearly every single day. We would spend hours scaling up sandstone in Clear Creek Canyon, and as we returned home my arms were limp biscuits and my face bore a great wide smile for the first time since my injury.

The days wore on in Colorado, and once again I wasn’t budging on the map. I got in touch with fellow Blackburn rangers Amanda and Iohan, who were down the trail and were expecting to meet up with me in Colorado or New Mexico. I informed them of my bum ankle, and that I wouldn’t be finishing the trail this season. The nighttime temperatures were in the 20’s, and I knew that if I took a month off to let my ankle fully heal, I risked freezing at night in the high mountains. Plus, I knew that if I let myself get back on the bike I would have trouble resisting the urge to pound out the miles as quickly as possible to catch up to my friends, which would only lead to disaster with my compromised tendon. I stayed with my stepsister for several weeks, enough time for Amanda to reach the Mexican border, return to Colorado (by plane), and come visit me in Golden long enough to grab a drink. It felt like I was staring in a mirror as I admired her sun-darkened shoulders and forearms that had sprouted muscles to steer our

the two-wheeled beasts that carried our tent, sleeping bag, water, gear, food, and clothing. Our time together was short, but it felt good to have some sort of closure to the trip by meeting up with someone who had accomplished the entire Great Divide, just weeks ahead of me. My mud-speckled Blackburn packs bore dirt from Canada, Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado, but they would have to wait until I was fully healed to bear dirt from New Mexico.

I fell in love with Colorado’s mountains and towns deeply and quickly and I wanted to stay forever. I searched for jobs in Colorado, but when a friend’s dad reached out to me with an excellent job offer in California to work for a recycling company, I realized that a bird was in my hand. I jumped on its back and rode it to the Bay Area for an interview, and realized that once again, I had to make a decision. I was moving to a less-than-exciting area of California that was a far shot from living in Colorado and exploring the nooks and crannies of the Rockies by bike and chalk-dusted finger tips, but I knew I couldn’t crash in my step sister’s bike room forever. I accepted the offer, boxed up my Niner, and flew back to California, where I am originally from.

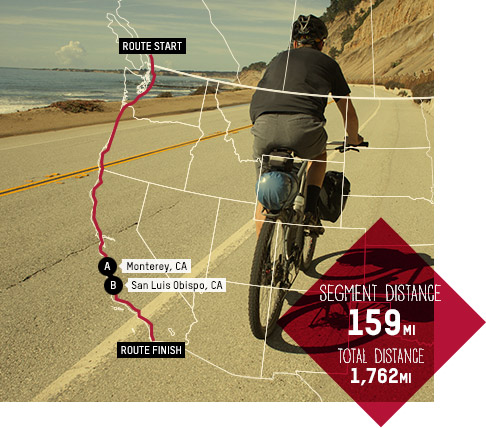

I’ve been off the trail for a while now, and time has softened the edges of the fact that I was unable to complete the Great Divide this fall. My Blackburn gear and Niner bike stood up to the rigors of the trail, but my body didn’t. In the heat of the injury, I had to convince myself that I wasn’t a failure for being unable to complete the entire 2,700 journey. Now, I look at the map I’ve pinned to my wall with its Sharpied line of my trip from Banff, Canada to Steamboat Springs, CO, and I realize how far I made it. I don’t see the trip for what I didn’t complete, but for what I did accomplish. I was alone for the majority of the trip, and there were nights when I lay curled in a cold ball at the base of my sleeping bag, knees and ankles sore, hands numb from the hours of clinging to handlebars that vibrated my nerve endings relentlessly, and I got up the next morning and hopped on my bike. Again and again I swore that there was no way that the next mountain pass could be more challenging than the last, and a

gain and again I was proven wrong. That being said, Union Pass was probably the most “memorable” of all the passes I struggled over.

I miss waking up under quaking aspen, curving along babbling streams, and staring into the sky and spotting bald eagles by day and brilliant constellations by night. I’m not a badass anymore. When I walk into a grocery store, I’m not dirt-caked with salt lines on my brow, and I have to remember a U-lock because people outside of the Wild West will steal your bike. I miss Wyoming, where cow hustling is more probable than bike theft.

What was the best part of my two months riding the Great Divide? Undoubtedly, the daily feeling of satisfaction as I squinted from atop a ridge, spotting a lake or a forest far in the distance that where I had eaten breakfast earlier that day. I crossed paths with black bears, coyotes, a very small handful of fellow Divide cyclists, and an even smaller handful of humans who weren’t just passing through the country on an epic bike trip- but who lived day in and day out in these rustic places with no cell phone coverage but freezers full of venison and elk that they hunted themselves and subsisted upon. I’m disappointed that an injury thwarted me from completing the entire length of the Great Divide this year, but I know that I will return at some point to accomplish it. This fall I learned humility in the face of adversity, as I congratulated my fellow Blackburn Rangers for completing the trip they set out to achieve, and I learned that some deer crave salt so badly that they will eat the padding inside your h

elmet in the middle of night to satisfy their hankering for a salty snack. I am so thankful for the opportunity from Blackburn to tackle the Great Divide this fall, and as long as the mountains remain, it’s only a matter of time before I return to the trail.

Happy trails,

Claire

- IMAGES OF THE ROAD -

Claire Porter

Gear List

- My Blackburn Gear -

- Sleeping Gear -

- • Tent (two person Big Agnes Fly Creek ultralight)

- • Sleeping bag (Sierra Design Zissou 23F)

- • Sleeping pad (Klymit Wave)

- • Pillow

- Eating Gear -

- • GSI plastic bowl

- • Spoon (a real metal one)

- • Knife (Opinel)

- • Stove (pocket rocket)

- • Fuel

- • Water filter (Katadyn)

- • Iodine Tablets

- • Water bladder (2L Platypus)

- • Food (a lot of peanut butter, dehydrated beans, ramen, and dried fruit)

- • Frying pan with lid

- Riding Gear -

- • Blackburn Outpost HV pump mini-pump

- • Tire levers

- • Tubes

- • Cyclometer

- • Adventure Cycling maps

- • Spare spokes

- • Spoke tool

- • Blackburn TOOLMANATOR 12 MULTI-TOOL

- • Spare screws

- • Headlight

- • Giro cycling shoes

- • Pedals (crank brothers candy)

- • GPS Spot tracker

- Clothes -

- • Jacket (Mamut with polartek sleeves…I love it)

- • Rain Jacket (marmot)

- • 2 jerseys

- • 2 chamois shorts

- • 1 pair fleece-lined leggings

- • Camp shoes (good ol' Sambas)

- • t-shirt

- • Flannel shirt

- • Cut-off shorts

- • 2 pairs of socks

- • 2 sports bras

- • Beanie

- • Sunglasses

- • Bandanna

- FUN -

- • Harmonica

- • Solar panel (Goal zero)

- • Ear buds (or speaker, not sure yet)

- • Smartphone

- • Phone charger

- • Headlight charger

- • Journal and pen

- • Mineral field guide

- • A book (yet to be determined)

- • Cycling Great Divide by Michael McCoy (with unneccesary pages ripped out)

- Clean -

- • Tooth brush and paste

- • Dr Bronners (TBD...not sure I really need to bring soap)

- MY BIKE SPECS -

- • FRAME-NINER SIR 9 CHROMO, 142MM X 12MM THRU AXLE

- • FORK-NINER SIR 9 RIGID, 853 (9MM QR) OR CARBON RDO (15MM AXLE)

- • FRONT WHEEL-SRAM ROAM 50 29

- • REAR WHEEL- SRAM ROAM 50 29

- • FRONT TIRE-WTB WOLVERINE 29

- • REAR TIRE-WTB WOLVERINE 29

- • INNER TUBES- WTB INNERTUBE PRESTA 29

- • SEALANT-WTB TCS SEALANT 500mL

- • CRANK SET-SRAM XX1 175MM

- • CHAINWHEELS-SRAM XX1 CNC-X-SYNC DRICT MOUNT, SEVERAL SIZES

- • BOTTOM BRACKET-SRAM GPX 73MM

- • CHAIN-SRAM-PC-XX1

- • REAR DERAILLEUR -SRAM XX1 X-HORIZON

- • REAR DER SHIFTER-SRAM XX1 TRIGGER SHIFTER

- • CASSETTE-SRAM XG-1199 10-42T

- • STEM-TRUVATIV STYLO T40 STEM SEVERAL SIZES

- • HANDLEBARS-TRUVATIV STYLO T40 RISER 700MM WIDE, 15MM RISE

- • TAPE / GRIPS-WTB TECH TRAIL CLAMP ON

- • SADDLE -WTB DEVA SLT

- • SEAT POST-TRUVATIV STYLO T40 SEATPOST 27.2MM DIA, 400MM LENGTH

- • FRONT BRAKE-SRAM GUIDE RSC POST MOUNT, 160MM ROTOR, >1,000MM HOSE

- • REAR BRAKE-SRAM GUIDE RSC POST MOUNT, 160MM ROTOR, >1,800MM HOSE

- • BRAKE LEVERS-SRAM GUIDE RSC

- • BRAKE HOUSING / CBL-SRAM

- •

Claire Porter

- FROM: Chicago, IL

- DOB: 1999-11-30

- OCCUPATION: Adventurer